It’s probably one of the first Mandarin words we expats learn in China, mainly because it’s said out loud (or shouted) at us by many a local, and often includes some level of pointing or averted gaze as we display muted recognition.

Yes, we’re of course talking about the term laowai.

A recent blog of ours, The Complete A-Z For Beijing Newcomers (or Visitors), described the term as “Chinese slang for ‘foreigner,’ often said out loud after having been spotted by a particularly perceptive local.” Our writer was also quick to point out an equally important aspect about the phrase: it’s a bit “contentious as some people consider it derogatory when used in a certain way, and literally means ‘outside old.’”

READ: A Guide to Getting Laid with Laowai. Really?

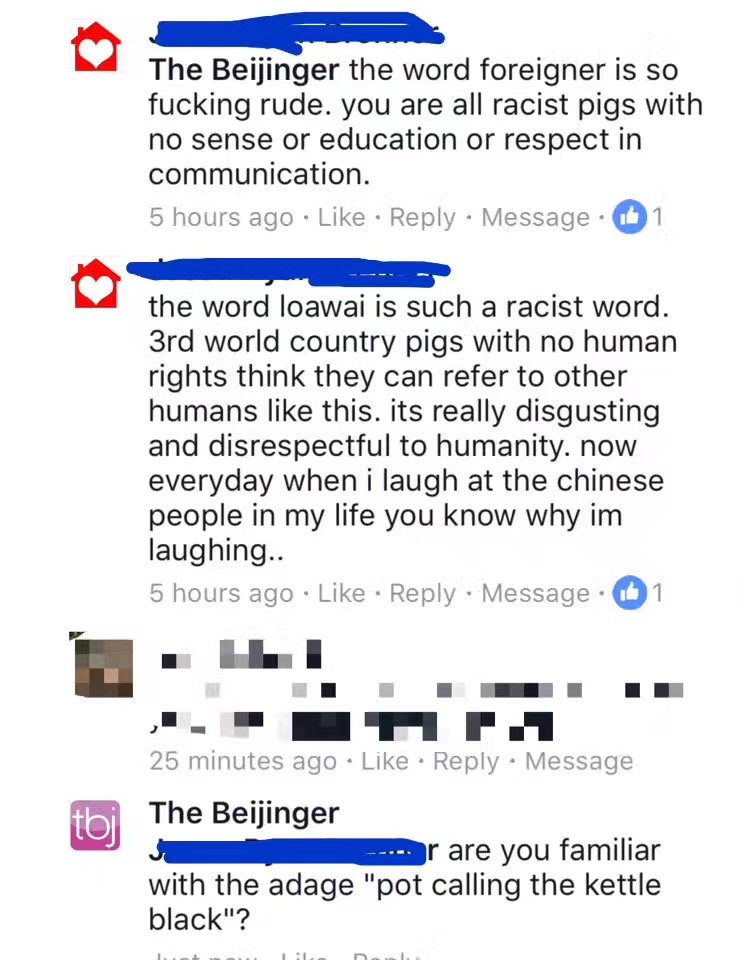

Many foreigners eventually become desensitized to such labeling, given the frequency of its usage, or shrug it off as meaningless from the outset. And yet there is still a surprisingly outspoken (albeit small and overenthused) portion of expats who are outraged by its utterance. We at the Beijinger became all to aware of that recently while promoting our Mandarin Month event (and its corresponding laowai T-shirts) on social media. This prompted one commenter to go on a very impassioned (and profane) rant against the term:

Other outraged readers insisted the term was racist, and a few even went as far as to call for a boycott of the Beijinger (but not before firing off some offensive slurs and inflammatory language of their own). Contentious as all this has become, it is by no means the first of such heated, laowai-related screed online. Anna Z, for instance, wrote on her Lost Panda blog (which she bills as an account “about life in rural China”): “It is time to stand up against a word that not just carries a derogatory connotation, but discriminates everyone in China who is not Chinese.”

She goes on to concede that such labeling is integral to the Chinese lingual structure. “In China you never only have ‘a friend’ (朋友 péngyǒu). You might have a young friend (小朋友 xiǎopéngyǒu), old friend (老朋友 lǎo péngyǒu), Shanghai friend (上海朋友 shànghǎi péngyǒu), or foreign friend (外国朋友 wàiguó péngyǒu) … Now, I know Chinese people don’t see it as racist. However, my point is with globalization and all, China has to pay more attention of its use of language, and so should their citizens.” That sentiment is echoed by numerous other bloggers in this roundup.

But Mudhun Ananthaiyer Ganesh disagrees. As an expat who studied Chinese at the Ideal Mandarin language center (we wrote about his story as part of last year’s Mandarin Month coverage), he attributes much of the issue to a lack of PC conditioning in China. He’d rather not waste time quibbling about it with his Chinese friends and colleagues, explaining: “Other foreigners who haven’t spent a few years in China may get offended by the term. But they will get used to it, and will learn to accept or ignore it,” advice that some may find hard to swallow.

Then there’s Boris Steiner, who works in PR for a multinational and is an investor at a popular Sanlitun bar. He thinks it’s “ridiculous” to be outraged by being called laowai because “at the end of the day I don’t think anyone means it in an offensive way,” though he admits it does annoy him on rare occasions.

Steiner’s friend Jiaming Xing – who interacts with plenty of foreign and Chinese patrons as the owner of the Gewa Qinghai noodle restaurant and the manager of Gongti hip-hop club Room 79 – agrees that there’s no reason to take umbrage with the term. “Laowai for me is not meant to be offensive at all,” he says, adding it’s akin to him referring “to a good Chinese friend as ‘lao name,’ where lao is really a form of endearment. Nothing derogatory at all.”

READ: Chinese Regionalism Joke Inspires Investigation of Whether Shanghai Expats Hate Beijing Expats

Chinese people aren’t alone in thinking the term is endearing. Dan Makowski, an American expat and fluent Mandarin speaker that has spent plenty a night trading woozy, good-natured barbs with Chinese and foreign pals at Wudaoying’s School Bar, used much of the same phrasing as Jiaming when asked about the term’s usage, adding “random locals referring to foreigners as laowai is as nondescript as it gets. If the people using the term don’t mean anything offensive by it, I don’t think it should be construed as offensive.”

Meanwhile Makowski’s friend Felix Liu, School Bar’s owner and a former Chinese language teacher, recalls with a laugh: “I’d always explain to my foreign students: laowai is a term that originated in Beijing’s local dialect, it means: 很亲切的外国人 (hěn qīnqiè de wàiguó rén, “very kind foreigner”) or 很有意思的外国人 (hěn yǒuyìsi de wàiguó rén, “very interesting foreigner”). But if someone calls you shabi laowai, then you beat them.”

Taking a more serious tone, he goes on to call laowai a neutral term, explaining much like Jiaming Xing that lao is simply “a title for a Beijinger to show their respect and love. Like, I call my wife Lao Wang, because her family name is Wang, or in the same way that I am Lao Liu to my friends. In Beijing, 老师傅 (lao shifu) means ‘old master,’ and 老板 (lao ban) means ‘boss.'”

After seeing such a clash of opinions for this story, I couldn’t help but consider how dramatically my stance on the issue has changed during my time in China. My wife’s parents in rural Inner Mongolia, for instance, would often call me laowai when we first met, much to the amusement of my friends back in Canada whenever they asked me to dish on the cultural clashes with my in-laws. It took some time for me to realize that it wasn’t because my father in-law couldn’t be bothered to remember my name, but that he was instead horrified by the prospect of offending me by mispronouncing it. It may have simply been that the combination “y” and “l” in “Kyle” isn’t an easy prospect for a fellow who has yet to learn “hello” in English.

READ: Red Dress Charity Run Attracts Online Controversy as Animosity Towards Expats Grows

And while the whole thing may seem pedantic, it spoke volumes about the differences in our sensibilities. It also lead me to be far more patient, empathetic and above all good humored, seeing as my father in-law now sounds like South Park’s Cartman whenever he greets me (who knew a one syllable name like “Kyle” could really be that tough to say?). It’s these instances of crosscultural bonding (and the chuckles that inevitably come with them) that allow for a welcome breather to the ever-escalating debates about political correctness, and in some cases, downright outrage, where neither side gets through to the other.

If you’re interested in finding out what the linguistic experts think, come along to our Mandarin Month Mixer this Saturday at Q Bar, 11am-3pm, and ask them yourself.

More stories by this author here.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @MulKyle

WeChat: 13263495040

Photos: sfu.ca, Lost Panda, Facebook, courtesy of Mudhun Ananthaiyer Ganesh